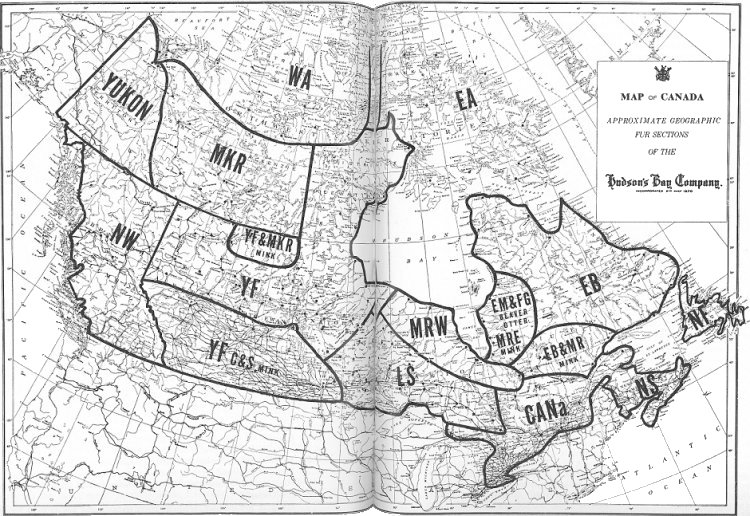

The preceding chapters have been devoted to the early mink ranchers, their organizations, their publications and their technical services. It seems only right that the object of all this attention, the mink, should have the opportunity to talk about the good old wild days. The ranch mink is the mixture of several Canadian mink races plus a few from south of the border. Its appearance in size, texture and colour is dictated by market needs and fashion whims. The native mink were some shade of brown and there were enough marked physical differences that taxonomists could classify at least five different races in Canada. Their Latin names and general geographical locations follow: (1) Mustela vison ranges through eastern Canada and would be the forerunner of the so-called "Quebec", "Labrador", "Nova Scotia" or "Eastern" types on the fur farms. (2) Another eastern subspecies, Mustela vison lowii, is found in northern Quebec and Labrador and it too may have entered into the types ascribed to M. v. vison. (3) Mustela vison lacustris occupied the Canadian interior from Great Bear Lake in the north and the western shores of Hudson Bay, south through Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the American border. (4) Mustela vison enerqumenos was a coastal mink found principally in British Columbia but did extend into adjoining Alberta and the Northwest Territories. (5) Mustela vison ingens occupied most of the Yukon and generally was considered the ancestral form of the large "Yukon" or "Alaskan" mink. The range of this subspecies touches that of Mustela vison lacustris, in the lower Mackenzie Valley and that of the Mustela vison melampeplus, near the base of the Alaska peninsula. It grades directly into these two subspecies. Probably all three of these sub-species have been used as breeding stock under the name of "Yukon". We had two sources for the above information - J. Walter Jones, Fur Farming in Canada 1914 and Robert K. Enders, Reproduction in the Mink 1952. As the early mink people began with locally caught wild mink, it is reasonable to assume that present-day mink have inheritances from all five original Canadian races plus one or more races from south of the border. The most probable of these would be the Mustela vison letif era which ranged from northern Wisconsin and northern South Dakota south to northern Illinois and Missouri, an area where many mink farms are located. It would not be correct to assume that the original races contributed equally to the makeup of modern mink. Even the early people raising their local wild mink soon learned there were better mink in some other localities and hastened to purchase them. The Quebec Eastern became the mink of choice, later to be replaced by the Western Yukon. These two breeds are the major components of modern mink. More recently, in the sixties, there was a trend to introduce large, heavily furred, wild strains of mink to increase size and vigour. It didn't last long but undoubtedly diluted the Quebec-Yukon inheritance somewhat. The Hudson's Bay Company incorporated on May 2nd, 1670, spread across Canada establishing fur trading posts in strategic spots. In time they began to notice that there was a similarity of qualities in pelts from one area that was recognizably different from another. This led to their fur graders setting up a system where Canada was divided into sixteen fur sections. As you will see in the map on pages 180 and 181, each section was labelled with a fur mark. These marks meant more than geographical location, they referred to specific qualities and appearance. Before we get into the official definition of these marks there are two facts we want to point out. First, mink weren't found in all these sections. We know that mink were not native to Newfoundland (N.F.). Yukon mink were not marked Yukon but were classed as North West (N.W.). We are not certain but we suspect that few if any, mink were classed as Western Arctic (W.A.) and Eastern Arctic (E.A.), and second in describing the fur marks the word 'pelt' refers to the leather, not the fur. To keep the record straight we'll give the remaining fur mark meanings as we interpret them. MKR is MacKenzie River, YF is Yorkfort, C&S is Central and Southern, L.S. is Lake Superior, MR is Moose River, MRW is Moose River West, MRE is Moose River East, EB is Eskimo Bay, Cana is Canada, NS is Nova Scotia and the last EM & FG means East Main and Fort George a mark used principally on beaver and otter. The Hudson's Bay Company has two general classifications for Canadian mink - Western and Eastern. In this definition, the west starts pretty far east. The dividing line runs south from the bottom of James Bay to the city of North Bay and then west to Lake Superior just north of Sault Ste. Marie. It is interesting to note that the fur mark descriptions seem to put the best first and poorest last in both classifications.

FUR MARKS Western 1. MKR (Mainly from the Mackenzie River District) Handled both pelt and fur out, this type is usually of average to broad stretch, very good size and quality, medium nap, and quite a good colour - better than that of other Western sections. 2. NW B.C. and Yukon skins, stretched rather long and narrow, medium to long-haired, good colours, usually handled hair out. 3. YF (Manitoba, Saskatchewan anal Alberta) VMedium to broad stretch, leather rather heavy and strong; good size; colours not particularly dark; rather long-haired. Handled pelt out. 4. LS (Ontario) LS mink are cleaner handled, lower napped and silkier than YF, with softer pelts of a creamy or soapy nature; sizes are smaller - usually handled pelt out. 5. MR West (Ontario) This is a "type" mark found amongst skins originating from posts on the west side of James Bay, and those Northern Ontario posts which draw collections from that area. In appearance the skins are somewhat similar to both YF and LS: the size is in between the two but it is longer haired than the LS, drier pelted and somewhat reddish-brown in both the guard hair and underfur - handled both pelt and fur out. 6. NW COAST This mark is broken into three main groups, very much according to the area of origin: (a) Northern Coast-from the Prince Rupert area. These have a long narrow stretch with a medium to long nap and are coarser in texture than regular NW. (b) Central Coast-from the central section of the B.C. coast, notably the Bella Bella and surrounding coastal area, as well as the North-Western coast of Vancouver Island. These are of good average size and somewhat broader in stretch than the Northern Coast. Colours are somewhat weaker. The nap is mainly medium with a texture akin to Northerns. (c) Southern Coast-limited quantities mainly from the East Coast of Vancouver Island, as well as the other channel islands. These are flat, coarse, hairy skins of poor colour generally. Most coast mink are handled fur out, have a fishy smell and open tails. EASTERN 1. EB EB mink are silky, plushy, of good colour and dense, silky underfur. They are usually handled pelt out. The pelts are medium in the stretch and of a soft parchment-like nature. 2. MR EAST AND LAKE ST. JOHN Somewhat similar to EB, but of poorer colour and more mixed in type. The underfur is not as dense and plushy as that of the EB. Handled both hair and pelt out. 3. CANA Superficially similar to the above, but longer-haired, coarser in texture, and not as good in colour. Pelts are sometimes fleshy and poorly handled. Two explanatory notes follow these definitions and both are interesting. The first says "All fine eastern mink are especially suitable for coats; the hair is not more than medium in length". The second deals with the sizes and sex differences of all Canadian mink. "Except for the finest Easterns, there is a marked difference in the size, texture and leather of males and females and, in the manufacture, they are often used for different purposes. The trade, particularly in North America, now prefers to buy them separately, classifying the males as XL and L (extra large and large), and the females as M and S (medium and small). Generally speaking, females realize 35-50% less than males". While the earliest mink ranchers were in the east and the ranchers from Manitoba on the west did not start until better than ten years later, the pattern was the same. Their first mink were local wild-caught animals. A glance at the Hudson's Bay fur section map and a slight knowledge of mink ranchers' locations will indicate the variety of mink. But what won't be apparent, is that while these mink in one section were generally similar, there was a wide variation in quality from one part of the section to another. Nowhere is this difference more obvious, than in the section called CANA. The CANA mink from southern Ontario were large, coarse, hairy, light brown types. The CANA mink from southern Quebec were smaller, finer guard haired, slightly darker brown and when taken in the Lake St. John area darker and almost silky. These better-coloured CANA mink from southern Quebec became the much sought-after breeding stock all across Canada. An interesting sidelight on the high opinion enjoyed by Quebec mink at this time is told by Frank Gothier of Anthon, Iowa and is recorded in the fourth edition of The Mink Book, R. G. Hodgson, author. "About 1923 there was a boom in mink ranching (in the United States) that brought in the promoter. The suckers spent their money, paying up to $500. a pair for mink, the pelts of which later when liquidated brought $3. each. Some of these ranchers built up to several thousand head in the United States. This was a black eye for the legitimate breeder. However, the 1929 depression closed up these ventures. Most of them used the native mink caught in Wisconsin, Minnesota and other states, and no matter how low the grade they still brought in $500. a pair on a ranch plan. Some were bought at $15 each, shipped to the Quebec district, and, by so-called cartwheel method, were shipped back to the United States for $100 and up, just for the simple reason that they were supposed to come from Quebec." The CANA section extended east to include the Gaspe peninsula and to merge with the N.S. section. There is no line of demarcation shown so we don't know where one ends and the other begins. Unfortunately, we have not found an official description for the N.S. section. Early literature places the N.S. mink on a par with Quebec. This is true about wild mink originating in Cape Breton Island but we are sceptical about mink from other parts of this section. Prince Edward Island wild mink were a hairy, flat-furred coastal type and we suspect there were more like them in other parts of the Maritimes. The very early P.E.I. mink ranchers quickly dropped the local mink and imported breeding animals from Cape Breton Island, Maine and Quebec. J. Walter Jones notes in Fur Farming in Canada that 50 live mink were imported in 1912 and 250 in 1913. At that time there were only seven ranchers keeping mink on the Island. Unhappily, we do not have export figures for P.E.I. for these years. But there is little doubt that some of these seven ranchers were buying wholesale and selling retail, to other parts of Canada. Nothing wrong with that, but it did lead to some inaccuracy when ranchers in other provinces advertised that they had P.E.I. mink. They never realized how lucky they were to have transients and not the native Prince Edward Island mink. In the late thirties, a few pale brown mink similar to what we now call pastels, showed up among the wild mink offerings at the January sales. I liked the look of them and became quite interested when I found that they showed up annually in the collections from the Lake of the Woods area in northwestern Ontario. The auction company provided the shippers' names and I wrote to them. The shippers weren't trappers, they were storekeepers who were fur buyers in the trapping season. Nestor Falls seemed to be the centre of the area so I went there and met several local trappers. They knew the pale mink only too well. The buyers paid poor prices for them. They were doubtful as to their ability to capture them alive. I offered what must have seemed big money and they agreed to try. Unhappily, nothing ever came of it. But there was to be an interesting offshoot from this search. One of the graders at the auction on learning of my lack of success in Nestor Falls said he knew where there were pale brown wild mink that could be easily secured. I couldn't find words to explain that I wasn't just looking for pale mink, but for a probable mutation where pale mink showed up in a normal dark mink population. It was easier to tell him to go ahead, which he did. Down in Cape Breton Island at West Bay, there was a mink rancher by the name of Donald Urquhart, who was also a trapper and had pale brown wild mink. The more I thought about it, the more interested I became. I got in touch with Donald and arranged for a breeding unit of these mink to be sent to Leitchcroft. They were medium brown, beautifully furred and somewhat larger than our dark Easterns. We kept them as a separate group for three years. They were the only pure N.S. mink I ever saw. In my opinion, they were much superior to the early Quebec (CANA) but probably they were better than the average N.S. mink as well. As the market continued to insist on dark mink we eventually pelted them out and lived to regret it. Two years later we brought in our first pastels and it still pains me to think of the qualities we might have developed out of the wild Cape Breton mink. In case you are wondering why we didn't go back to Donald Urquhart and buy more, the answer is easy. We did and Donald told us he had pelted out this portion of his herd. Further, fugitive dark ranch mink had so altered the wild mink population, that the N.S. mink character could no longer be found. In the 1930s, two matters of questionable importance occupied the mink ranchers minds. They were pursuing blue underfur and a will o'the wisp called Labrador mink. We will deal with the blue underfur first because its story is less complicated. Bear in mind that this is the thirties and the only kind of mink, ranched and wild, is some shade of brown. Beautiful pale blue underfur did exist, but only in association with pale brown to beige coloured mink. Many of our northern Quebec wild mink are of this colouration and the underfur is blue. The tips of the blue underfur fibres are beige and together with the light brown guard hairs give the pelt a pale appearance. In a collection of fur from this area, the mink will vary from pale to dark. On examination, you will find that the blue changes and disappears very quickly as you progress from pale to darker shades. It quickly becomes grey and gradually deepens until it becomes a slate to almost black grey in the darkest pelts. We would have been happy if this colour progression applied to the ranched mink but it didn't. Noah probably had more animals in the ark than the rancher had strains in the ancestry of his mink, but not many more. In the rush to get darker mink, few people looked at the underfur. Grading was usually an aeroplane view from above the pen to determine darkness. Left to its own devices, underfur assumed some weird mud shades from yellow, through red, to orange. The very darkest mink had an interesting rusty cast to the underfur that didn't prevent them from taking the top prizes at the shows. The fur trade was less kind than the show judge and refused to pay good prices for poor under colour. They told the ranchers that they wanted blue under colours. What they meant was clean, clear under colour. Ranchers spent a lot of time imagining they saw blue but ultimately ended up with better undercolour when they got into the western-type mink. At Leitchcroft farm we were well aware of the problem. We also found that the underfur colour was not uniform from one end of the mink to the other, It tended to become paler towards the head. This made comparison grading difficult because it was questionable whether you were looking at the identical area on each squirming mink. C. O. Ashwell solved that problem when he built us a squeezebox that imprisoned the mink and allowed us to examine an exact area on all our animals. As our mink were not more than three generations removed from the northern Quebec wild, we had some attractive undercolours to develop. One female had an especially blue-grey underfur, but an inhibition about motherhood. After two disappointing years, we pelted her and entered her in the 1941 Ontario Pelt Show. That show was the largest ever held in Canada, attracting 2,303 mink pelts. The reason was that the show pelts were afterwards sold by auction and brought premium prices. Mike Rosenthal, a very real authority on and purchaser of Canada's top-quality wild and ranch mink, was the judge. Calvin Martin, Russell Griffith and I were on the classification committee and after segregating the pelts in their classes our job was to fetch and carry them for the judge. Because of the number of pelts in the four single-entry classes, Mike decided to do a preliminary run-through and discard all but the top pelts. When he came to this blue underfurred female in the adult class he became very excited and wanted to know whose mink it was. It was my mink, but the cardinal rule in a pelt show is that pelts carry only a number for identification. This assures the exhibitors of fair play and protects the judge from accusations of favouritism. We had a lively, but, uneasy few minutes until we persuaded Mike to go back to grading and leave the identity of the mink until after the judging was completed. Mike made this mink pelt adult Female Champion and later Grand Champion of the Show. He told me after I was identified as the owner that this was the first time he had ever seen an E.B. wild mink type raised under ranch conditions. Unfortunately, we were never able to produce quantity in this desirable under-colour and eventually replaced these Easterns with western mink, which while not producing blue still gave us a cleaner, clearer underfur. Later, in the 1940s, a genetic variation in dark mink gave rise to a two-tone mink. The underfur was off-white and the guard hair remained dark. The early producers did well-selling breeding stock. The first year that these so-called blue-furred mink were offered for sale, the furriers paid good money. To their dismay, the garments were unattractive. This type turned out to be a cotton mink which, from the furrier's standpoint, was the kiss of death. They promptly disappeared from the fur farm scene. The literature of the 1930s, is enlivened with accounts of the myth that never became a mink - the Labrador. Of course, if you want to be pragmatic any mink found in the territory of Labrador, whether it was a hairy coastal type or a fine interior, would be a Labrador. But that wasn't the rancher's interpretation. They believed that in this northeastern wilderness existed a super mink, the possession of which would guarantee fur farming success. No description of this paragon of the mink world existed. The ranchers' belief in this mink was like their belief in heaven. They were sure of its existence and excellence but uncertain as to its appearance. We'll get around to the stories of the few venturesome ranchers who penetrated this wilderness seeking the fabulous Labrador later in this chapter The Hudson's Bay Company's system of fur sections, called the Labrador and all the rest of Northern Quebec, E.B. This meant Eskimo Bay, possibly a fur trading post in earlier times, but now the general fur name of this vast scantily populated area. If you will examine the map carefully you will see there is a central plateau or watershed just to the west of the E in E.B. The rivers originating here flow in all directions. As there are few outposts in this section, the trappers brought their furs to the trading posts on the coast, after the break up in the spring, when the streams were navigable. This meant that E.B. mink pelts, Hudson's Bay's top eastern quality, not only showed up at Labrador posts but also on the Gulf of St. Lawrence and at posts north and west of Lake St. John. They were never very numerous, probably no more than 2,000 pelts in the best of years. They varied in colour from pale to dark but as ranch mink prospects, they were too small and too pale, for domestic purposes. But they did give rise to the fable of Labrador mink when they came down to that coast to go to market. Don C. Bremner of Pasquia Fur Farms, Veillardville, Saskatchewan spent several years buying furs for the Hudson's Bay Company in E.B. country. Writing in the February 1939 issue of the Fur Trade Journal of Canada, he gives a factual description of the trade and tends to locate the trapping area near the central plateau which he refers to as the 'height of land.' "About the end of June the Indians commenced to arrive at the outposts and the staff is fully occupied trading for their winter's hunt and making preparations to ship the fur collection to the parent post on the coast. An experienced river man is first chosen, who is responsible for the selection of the crews for the various canoes required for the trip. This is done, equipment is made ready and the outpost is closed for the summer. All is now excitement, for this means that the Indians are to see their relatives and friends whom they have not seen since the previous summer. But first, there are many dangerous rapids to be run and it is here that an experienced riverman is necessary to lead the whole brigade through in safety. On arrival at the parent post, a dance is held and after a few days of visiting, they settle down to the summer's work. "Canoes and equipment are now prepared to freight supplies to the various outposts inland. Each native is responsible for 500 lbs. of merchandise which is loaded into 24 ft. canoes carrying a total weight of 2000 lbs. of merchandise which is added equipment and rations for the duration of the trip. A canoe of this type has a crew of four men and it is nothing unusual to see as many as ten canoes of this size and a larger number of 18 ft. canoes, each capable of carrying 1000 lbs. of merchandise and equipment for two men, leaving the various posts for ten to fifteen days of arduous labour upriver to the outposts. Some of these rivers are so rough, that they necessitate as many as fifty portages before the brigade arrives at its destination. Peculiarly enough, they enjoy the work and compete with each other in the size of loads they can carry over a portage. "On their return a feast and a dance is usually held. There the 'Company' store is the centre of attraction. Payment is now made for all work done and most important they take up their 'Debt' in supplies which will carry them through the coming winter. The best hunters are advanced as much as $1500 in merchandise. By the end of August, they have their outfits completed and are on their way to their winter hunting grounds. The majority of them travel by canoe and snowshoe until Christmas time, hunting and fishing for a livelihood, until they reach their chosen locality, which is usually in the proximity of the `Height of Land'. "There they meet Indians who have penetrated from the northern slope of the St. Lawrence Valley, all in quest of these fine quality mink. The Nitchequon area in which these natives hunt, so-called after a post established there by the Hudson's Bay Company many years ago (which was recently re-opened, the supplies being taken in by air) is commonly called 'Height of Land'. The lakes here give rise to rivers flowing in all directions, to Hudson's Bay and James Bay in the west, to Hudson Strait and the coast of Labrador in the north and northeast, to the Gulf of St. Lawrence in the east and the St. Lawrence River Valley to the south." The only mink we knew to be offered for sale from the Nitchequon area of northern Quebec was bred by Major L. D. McClintock. He called them Ungava and the advertisement for them appears in the September 1937 issue of the Fur Trade Journal of Canada and is quoted in full in that part of the Quebec chapter dealing with McClintock. When the Labrador mink fantasy became popular, Major L. D. McClintock wrote a down-to-earth article on the subject, entitled The Labrador Mink, in the November 1930 issue of the Fur Trade Journal, parts of which appear in the following quote "When I tell you that to the best of my knowledge, I am not sure that I have seen any genuine live Labrador mink, perhaps some readers may be surprised that I should undertake to write on the subject at all, but as I have been keenly interested and at every reasonable opportunity have studied mink pelts and live minks during the last ten years or so, I make so bold to hand on my opinions such as they are. "I have seen mink that their owners, whom I ordinarily would consider, to be honest enough, said were the genuine Labrador stock with all sort of circumstantial details to back up their claims. However, up to date, I have only seen about three alleged Labradors that would even be classed as fair, and I frankly doubt their genuineness. "While I have probably never seen any wild minks actually from the Labrador, I have seen many Labrador pelts in the warehouses of such concerns as the Canadian Fur Auctions Ltd., Holt Renfrew and Co. and the Hudson's Bay Company. While I feel safe in saying that none of the Labrador pelts seemed quite as dark as the darkest Eastern Townships Quebec mink, the best of the Labrador pelts had a characteristic silkiness and a wonderful depth of underfur. This is what is characterized as EB quality which is the top-notch of mink fur classification in the fur trade; but EB quality is not met, in all Labrador pelts. On the other hand, EB quality is to be found in the best grade of pelts coming from other sections of northeast Quebec adjacent to the Labrador proper. "In fact, to the best of my belief, if pelts are a basis for judgement of what live Labrador mink should be like, I would say that Labrador minks on average are much the same as those from around the Lake St. John, Peribonka River and that general region. In the course of the last few years, I have seen quite a few live wild mink from the latter parts and while in common with many Labrador pelts, they average somewhat lighter than we could wish for, they run as a rule exceedingly silky as to guard hair, and dense, deep and fine as to underfur. I have said that the pelts from those northeastern parts of Quebec are often not as dark as one could wish for, but on the other hand, their colour is usually clear, with a slatey dark ash shade to the underfur, and no suggestion of redness". In the April 1933, issue of the Fur Trade Journal of Canada, there's an article entitled "The Solution of the Labrador Mink Mystery' written by R. T. C. Corfield from which we take the following extraction. "As I suppose most people know, Labrador is a narrow strip of land which runs northward along the Atlantic coast from the Strait of Belle Isle in the south to Hudson Strait in the north; this is not where the best mink come from, but they are found in a very few distinct districts in the Labrador Peninsula. (probably Corfield means the interior comprising both Labrador and northern Quebec territory) "I think this is the cause of a great deal of misunderstanding; as an example, take Lake St. John mink which are generally classed as northern Quebec, whereas mink from the headwaters of the Peribonka River, which flows into Lake St. John, are known as Labradors. There are only three or four districts where the fine Labrador mink are found. The headwaters of the Peribonka River is one good district, the Hamilton River is another, and there may be one or two more, but with these exceptions, the average run of Labrador mink is not as good as the average mink found in Eastern and Northern Quebec." The man who focused the mink ranchers' attention on the Labrador was T. C. (Cam) Richardson, Fergus Fur Farms, Fergus, Ontario. Cam was a dedicated outdoorsman and the elusive Labrador mink fascinated him. He established a ranch at Bradore Bay in what Quebec calls the Cote-Nord (North Shore) near the southwest end of the Strait of Belle Isle and within a few miles of the ill-defined Quebec-Labrador border. No doubt Cam thought he was in Labrador and as far as we are concerned he was. But in case you are doubting Thomas with a large-scale map of the area, we have been as precise as possible. How long the Bradore Bay Ranch, as a producer of live mink, existed is not recorded too clearly. The first joint advertisement with Fergus Fur Farms appeared in the August 1930 issue of the Fur Trade Journal of Canada and continued until the end of 1931. In 1932 while Labrador and Northern Quebec mink continued to be advertised the Bradore Bay identification disappeared. Its only reappearance, we could find, was on a brochure produced by Fergus Fur Farms on mutation mink in the 1940s. In the December 1930, issue of the Fur Trade Journal of Canada, there is a letter to the editor from T. C. Richardson which is interesting "We have completed the purchase of the property at Bradore Bay and we now have forty-four acres of fairly level sandy land. An excellent spring creek flows directly through the property. Mr Aitken has been able to secure enough trout from this creek to feed what mink he had all summer. On the property, there is an excellent eight-roomed house, post office, store, warehouse and seal fishery. We have now constructed one hundred pens in somewhat the same style as those at Fergus. We have added five pairs of silver foxes to the ranch recently. "Mr Sid Aitken is in charge of the animals and Mr Alphonse Blais operates the post office, store, etc. The last boat left on October 29th, so they will be without service for over six months. Owing to the very few fish being caught, we have been obliged to send a six-month supply of food for the animals on this last boat. We had not anticipated this difficulty and found it very expensive. Mr Aitken has secured several wild ducks to supplement the feed and this is about the extent of the food from local sources this year. We have been rather disappointed in the number of wild mink we could secure but hope since trapping has commenced, we will get more. "What mink we have got have been of good quality and from good districts. We had Mr Aitken send us one female from Red Bay near Hamilton River, about seventy-five miles north of our ranch. We recently made a trip to Quebec to receive this mink and also visited the Lake St. John district. We have her now on exhibition on our ranch along with a pair of wild-caught Lake St. John district mink which we purchased from trappers while there. Anyone who says they are the same animal I am sure has never seen a genuine Labrador mink from the best sections. There is a great difference in size, texture, length of hair and colour. We welcome anyone to come and examine and compare these mink at our ranch and see for themselves a live sample of the mink for which the fur trade pays the highest price. "The most noticeable difference between the Quebecs and the Labradors is in the texture and length of fur. The guard hair and underfur are very fine and soft, and the fur appears somewhat shorter, as near as I can explain. It has the appearance of a good Quebec when it is hardly prime. Many who have viewed this mink have asked if it is fully prime. "The colour is extra dark, with a slightly bluish tinge to the underfur and a glossy black to the guard hair. We have darker Quebecs but they do have not the rich appearance as the full Labrador. The colour is very even and they are almost as dark underneath as along the back. There is no appearance of coarse hairs at the butt of the tail and the back of the legs. In size, they are somewhat larger than the Quebecs. They appear slim and long, with good length of the tail in proportion to the body." There is no doubt that T. C. Richardson had all the instincts and abilities of a good showman. In the same issue as the above letter, the editor notes "There was considerable of a showing of fine minks at the Royal Winter Fair (Toronto, Ontario) of which perhaps the stand of Fergus Fur Farms attracted the most attention. Located on one corner of the line of booths headed for the fox show, the large painting showing their ranch at Bradore Bay, Labrador, commanded immediate attention. The artificial pen with running water (presumably occupied by mink) was a considerable feature and great crowds were attracted to the stand." At this point, we have to inflict a history and geography lesson on you but we'll try to make it as painless as possible. During the period under discussion, Newfoundland was not a province of Canada but a Crown Colony of Great Britain and Labrador was considered a part of Newfoundland as it still is today. Geographically Labrador resembles an isosceles triangle drawn by a person suffering from hiccups. The top is at the Hudson Strait, the two long sides are about 700 miles long, and the southern base is a straight line just over 400 miles long. It lies between the 52nd and 60th parallels of latitude and at its widest a little above its base it stretches west from the 56th to near the 68th degree of longitude. This leaves a strip of Quebec to the south of the 52nd parallel of latitude some 130 miles wide, that extends from near Baie Comeau, east to the Strait of Belle Isle, which is called Cote-Nord (North Shore) by Quebec and sometimes Canadian Labrador by the fur people. This leads to confusion as to what Labrador is meant. References to Northwest River, Hamilton River and Cartwright are Newfoundland and Labrador. The rest are probably Cote-Nord and Northern Quebec references. In the October 1932 issue of the Fur Trade Journal of Canada, T. C. Richardson mentions his third visit to the ranch at Bradore Bay that year and then proceeds to describe his visit of the year before to the Labrador hinterland. It is specific as to topography, miles travelled, trout caught and time spent but vague as to the numbers of wild mink captured which was the purpose of this arduous trip. The latter part of the article contains interesting information which we quote - "For the past three seasons we have been extending every effort to secure all the live Labrador mink that we could. We now have a nice herd of Labradors. We have never sold a single Labrador to date as we have, up to now, been unable to get enough for our requirements. We believe we have the only live mink out of Newfoundland Labrador and practically the only ones from Canadian Labrador. "To our knowledge, there are two Labrador mink at Cartwright, owned by the Hudson's Bay Company and one belonging to a gentleman in Newfoundland; as far as we could learn they had no increase to date. These we believe are the only ones in existence outside those we have exported. In October 1931, we imported eleven Labrador mink from Newfoundland Labrador via the port of Blanc Sablon (Cote-Nord) and one via Port aux Basques (Newfoundland) from Canadian Labrador. "In 1930, one mink was purchased at Old Fort (this and the following place names are all in Cote-Nord) and the owner told me he had no increase from her. The Hudson's Bay Company at Havre St. Pierre also secured one from Natashquan and to date, they had no increase. Last fall, 1931; one was taken at Natashquan, two at Old Fort and one from St. Augustin River. The one from St. Augustin River was caught only some fifteen miles in the mouth of the river and I can vouch that this is the only mink to go from the St. Augustin River other than those taken by ourselves. "We have made an honest effort to secure real Labradors and we have them. But where did the others come from? I cannot find that they came from Labrador". T. C. Richardson did not have to wait long for an answer to his question. In December 1932, an issue of the Fur Trade Journal of Canada, under the heading of `Where do the others come from?' an unsigned article, which we believe was written by Dr J. E. Laforest, gave him the information. Some of which he didn't seek. We quote the article in part. "Mr Richardson of the Fergus Fur Farms, gave us an account of his trip on the North Shore and his trapping experiences, in last month's issue of the Fur Trade Journal. These experiences led him to the extraordinary conclusion that the only mink coming from Labrador, outside of one unknown proprietor, is the exclusive property of Fergus Fur Farms, operating at Fergus, Ontario, and Bradore Bay. By the way, the ranch at Bradore Bay, according to personal investigations, containing a few wild mink, besides the Ontario mink shipped up there some time ago, is now sold and belongs to Capt. Blais. "We believe that Mr. Richardson has a few Labrador minks, and we congratulate him, but this does not exclude the fact that the Kingdom of Labrador mink does not, by a long shot, belong to him exclusively. Instead, he should be trying to unite with other breeders having the same quality of mink, showing them at his ranch so that breeders away down in Ontario can see what a Labrador mink looks like. So far, the only Labrador mink seen down there is a dark brown Hamilton River female. He gave prospective customers a wrong idea about the very type of mink of which he is boasting. Refer to his description of a Labrador mink in a previous article `A Labrador mink looks like an un-prime Quebec mink'. Good gracious we never saw a Labrador mink of that type here. "To our best knowledge, the main difference between a Quebec and a Labrador is in the fullness of the fur, the latter having a deeper, fuller and perhaps bluer tinge than the best Quebec mink. "Refer to the October issue of the Fur Trade Journal (1930) where Mr Richardson says that he is making direct shipments from Bradore Bay with pedigrees furnished. And now he claims he has not shipped a single Labrador mink yet. "A few particulars about Labrador mink sections, as recognized by the fur trade in the east. The best sections for Labrador mink and the place where the best mink in Canada are found are in the headwaters of the Peribonka, Betsiamite and St. Augustin Rivers - in other words in the Canadian Labrador. The Newfoundland Labrador does not produce as fine or as silky a mink, though this section is further northeast. For further confirmation ask any of the well-known furriers, fur buyers or government experts. According to Mr Richardson all live mink caught in the Canadian and Newfoundland Labrador are reported to him, a territory twice the size of the province of Ontario. Well, he is slightly mistaken. "Clairval Ltd. has either purchased from Indian trappers or indirectly or trapped, in the last four years, 38 females and 15 males from either Peribonka, Betsiamite, Outardes and St. Augustin River headwaters. The last shipment direct from St. Augustin River included three females and two males was received at Quebec (city) directly from the steamship company with an affidavit. Note that these wild minks were neither extra dark nor snowbirds. Today Clairval Ltd. has 200 pure Labrador mink of which two-thirds are extra dark. "Laforest Fur Farms has since 1930, purchased seventeen mink from Labrador, either from Tonnerre River, Hamilton River via airplane direct to Quebec (city) and from Beetzos Bay (Baie Johan Beetz) all in the Canadian Labrador (except Hamilton River). Today, Laforest Fur Farms has fifty-seven pure Labrador breeders of which twenty-one are extra dark." In the November 1932 issue of the Fur Trade Journal of Canada, the editor Bob Hodgson says "We were talking recently to Mr. (Frank) Hayes of the Hudson's Bay Company who spent some time in Labrador the past summer and he informs me that one of their posts in Labrador has a very fine bunch of Labrador minks which they are successfully propagating." O. K. Thomassen in a delightful article entitled "Jimmy Williams" published in the August 1940 issue of the Canadian Silver Fox and Fur, not only entertains us but supplies some solid facts, of which we are much in need. The subtitle is a necessary introduction to the article so we quote it "Hudson's Bay Fur Farm pensions off a faithful servant - Jimmy Williams - the mink patriarch. Now lives a life of luxury and contentment on the Bird's Hill (Manitoba) ranch." And now we'll let the talented O. K. Thomassen tell the tale. "To the majority of western fur farmers, Jimmy Williams is but another name - an unknown. In the Fur-farming history, however, of the `Company of Gentlemen Adventurers' and to those in the know, Jimmy Williams is more than a name, it signifies the blue blood of the Bay minks, the patriarch - the venerable chief of the mink herd. "In a special, circular cage, painted white, placed conspicuously near the main entrance to the Bay mink farm, resides Jimmy Williams, a little weary but contented and feeling immensely important. "Jimmy was born at Cartwright in the Newfoundland Labrador area sometime during the spring of 1928. On January 14th, 1929 he was purchased by the Hudson's Bay Company. The same year he met and was introduced to his first great love, a three-legged Labrador female. As a result blossomed forth three sturdy Jimmy juniors, who together with their dad, became the foundation sires of the Hudson's Bay Co. herd, which when it was moved to Winnipeg in 1933, consisted of eighty-six minks. Jimmy, although then looking after a big harem, was still, in a sense, true to his first mate, the three-legged one. Each year, until her death in the spring of 1936, he was the father of her litters, representing in all thirty-seven kits. "While the straight Labrador minks are not of a dark colour, they possess a fine silky texture and Jimmy Williams direct progeny exceptionally so. Following the building of the present ranch in 1934, the Bay introduced some very fine, dark Eastern-type minks. These blended in beautifully with the Williams' offspring, producing the majority of the real outstanding minks in the Bay herd, now numbering more than two thousand animals. "In 1937, three of Jimmy's offspring were bought by an English breeder. A friend of this gentleman had visited the Bay ranch and must, upon his return to England, have extolled the virtues of the Jimmy Williams' tribe very effectively because the breeder cabled pronto to Winnipeg offering a fancy price for a trio, an offer which I suspect was equally pronto accepted. Shortly following the arrival of the trio in England, one of the females died. The English breeder must have liked the minks as he immediately cabled at his own expense, purchasing the fourth mink. By the way, one of these females later was awarded a championship at a British fur breeders show. "Jimmy Williams has during his long life sired a great many litters and it is only during the past two years that his age has got the better of him. Last year he left no litter, and this spring he was not used at all. As a reward for his long and faithful service, in the Company's interests, he is now a pensioner of this famous organization. When Jimmy sometime in the dim future decides he has had enough of this world and sets out for the happy hunting grounds promised to all deserving minks, he will as a last service to mankind, contribute his head to the scientist, Ch. Elton, an animal researcher at the Oxford University, England. He has requested that Jimmy's cranium be sent to him for study, in the hope of discovering why Jimmy should have lived so much longer than his brethren." In the February 1933, issue of the Fur Trade Journal of Canada, Major L. D. McClintock made the following penetrating observations. "My advice to the keen mink rancher is not to get all steamed up over any fancy breed name. Get to know what to look for in mink fur. A good way to do this is to go on a straight pelt basis. "My own opinion is that the hectic scramble based on livestock selling exclusively has gone just about far enough. What the fur trade wants is pelts, and it is up to us to produce better and better pelts from year to year. Let us all fancy our pet breeds whether they be Alaskas, Labradors, Yukons, Kenai's, Nova Scotias, Quebecs or what have you, but let them stand or fall on a pelt production basis." The Major was a true prophet. The day when ranchers could rely on the sale of live mink at inflated prices to keep their operation profitable was rapidly coming to an end. By the last of the thirties, most ranchers faced the inevitable - it was pelt or perish. For many, the outbreak of World War II was the last straw and they pelted out. Thus we come to the end of our history of the mink industry when live mink sales were the whole purpose of the business and we leave to others the history of the second phase when pelts became the thing. |

| Deep River Fur Farm |

| Deep River Trapping Page |

| Deep River Fishing Page |

| My Norwegian Roots |

| Early Mink People Canada - Bowness |

| The Manager's Tale - Hugh Ross |

| Sakitawak Bi-Centennial - 200 Yrs. |

| Lost Land of the Caribou - Ed Theriau |

| The History of Buffalo Narrows |

| Hugh (Lefty) McLeod, Bush Pilot |

| George Greening, Bush Pilot |

| Timber Trails - History of Big River |

| Joe Anstett, Trapper |

| Bill Windrum, Bush Pilot |

| Face the North Wind - Art Karas |

| North to Cree Lake - Art Karas |

| Look at the Past - History Dore Lake |

| George Abbott Family History |

| These Are The Prairies |

| William A. A. Jay, Trapper |

| John Hedlund, Trapper |

| Deep River Photo Gallery |

| Cyril Mahoney, Trapper |

| Saskatchewan Pictorial History |

| Who's Who in furs - 1956 |

| Century in the Making - Big River |

| Wings Beyond Road's End |

| The Northern Trapper, 1923 |

| My Various Links Page |

| Ron Clancy, Author |

| Roman Catholic Church - 1849 |

| Frontier Characters - Ron Clancy |

| Northern Trader - Ron Clancy |

| Various Deep River Videos |

| How the Indians Used the Birch |

| Mink and Fish - Buffalo Narrows |

| Gold and Other Stories - Richards |